Why "A Country Without Borders Will Cease to be a Country" is a Deepity

It rests on the rare “Argument from Homonym”, also known as the equivocation fallacy

Kristi Noem (Secretary of Homeland Security): “Our nation is a nation with borders, or we’re no nation at all…”

Tom McClintock (US Congressman from California) : “A Nation Without Borders Will Cease to be a Nation”

John Kerry (2004 Democratic candidate for president): “without a border protected, you don't have a nation”

Donald J. Trump (real estate mogul and American politician): “Without borders, we don't have a country”

Watch any immigration debate and chances are, someone will whip out: “If you don’t have borders, you don’t have a country.” It’s a slogan that’s rhetorically effective, seemingly profound, and completely false.

It’s a powerful political statement, but it ultimately conflates two very different arguments: one based on a linguistic sleight of hand and the other on the potential consequences of immigration. The first interpretation is rhetorically powerful but logically incoherent. The second, while often based on contentious assumptions, can lead to more substantive debate.

A Tale of Two Borders

The “definitional” argument goes something like "Countries are defined by their borders. That's the way it's been for most of human history. If you don't enforce border restrictions, then the borders de facto do not exist. Thus, definitionally, you do not have a country.”

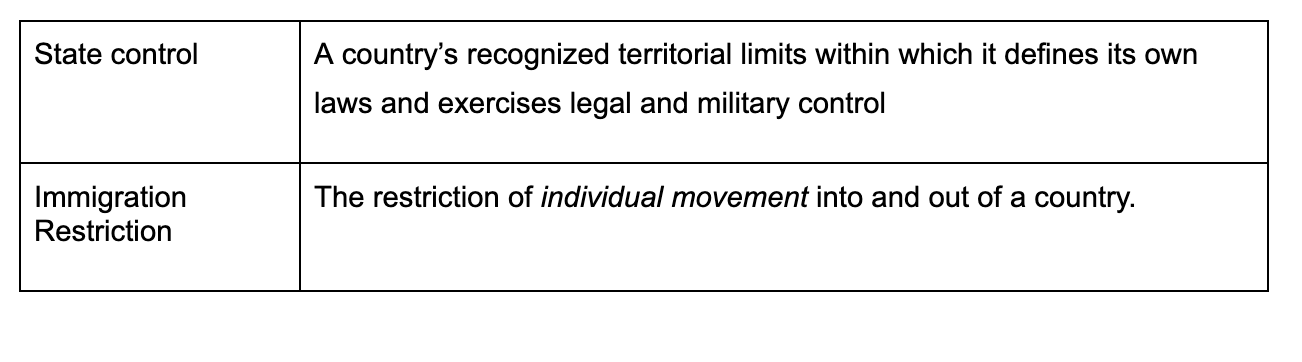

The "definitional" argument’s fatal flaw is that it conflates two distinct concepts of a "border":

A Brief Historical Perspective

Historically, the existence of a country has been defined by the first concept, not the second.

Traditionally, borders were about State Control (for example, who the state can levy taxes from and/or levy into soldiering or other forced labors, which mines or other natural resources can the state exploit, where the state can/can't send its military).

For most of human history, Immigration Restriction at borders was practically impossible for most states. Attempts at such were usually during extreme circumstances (e.g. pandemics), and usually only for population centers, not for all of the states' official boundaries.

In the modern (State Control AND Immigration Restriction) sense of "borders" that people are often referring to, borders were not enforced for most of human history, and yet countries definitely existed before the 1800s.

Consider1:

The Roman Empire. The Roman Empire’s border guards were a) sporadic, and b) meant to warn of (and defend against) military invasions. The Roman Empire had very little ability or inclination to prevent the free movement of goods and peoples. Yet most people consider the Roman Empire to be a real thing, and indeed men even think about it often.

Similarly, other ancient empires often limited citizenship but rarely restricted movement.

Pre-1870s United States: Before a series of racial restrictions in the 1870s that culminated in the Chinese Exclusion Act (1882), the US did not do significant immigration restriction2. Yet historians have no trouble dating the United States from 1776 (or 1789). Even very right-wing historians do not consider the US’s founding to be 1882.

(Modern) The Schengen Area: The 29 European states in the Schengen area allow for the free movement of people without border controls between member states. The countries nonetheless have distinct jurisdictional boundaries, have their own laws, flags, and soldiers, and exercise their own jurisdictional and administrative controls within their own countries.

Bordering On Deepities

Thus, the slogan 'if you don't have borders, you don't have a country,' when used this way, is a linguistic trick based on a fallacy

It invokes and sneaks in the connotations of BordersStateControl to get you to agree with BordersImmigrationRestriction. It is a reasonable claim that a country that has limited state power and cannot take normal state actions like levy taxes or move its military within its supposed borders is not much of a country, as traditionally defined. At best, one might call it a "failed state."

It is a much less reasonable claim to extrapolate intuitions and connotations of BordersStateControl to assert an ahistorical claim like countries that don't have BordersImmigrationRestriction in the sense of a strict immigration enforcement are somehow failed or non-existing states.

Ultimately, the “definitional” argument is essentially an Argument from Homonym, which is honestly a pretty funny logical fallacy to consider3.

We should understand it as a deepity: a statement that has two interpretations: one that is true but trivial, and another that is false but would be significant if true.

Of course, some people who use the slogan are just invoking hyperbole to say “immigration bad.” And there are legitimate debates about immigration policy and its effects on national character, institutions, and culture. But those are empirical arguments, not definitional tricks.

Think Actual Thoughts, Not Shallow Facsimiles

I’m not against slogans, or simplifications. I often find them quite charming, and useful. The political world is a complex and sometimes confusing place.

It’s very valuable to have the ability to distill a complex argument or concept into its simple core, so you can understand it better yourself, explain it simply to others, use the concept as a lemma in future arguments, form a shared understanding of the world so you can coordinate better on social change, etc. Indeed, much of what I hope to do with this blog is making seemingly-complicated ideas simple.

But in making such simplifications, it’s very important to make sure you’re actually simplifying the essence of an argument, and not just manufacturing a fake argument in its place. And when repeating someone else’s simplification or slogan, it’s often important to do spot-checks and make sure the simplification or slogan can actually expand into a real argument, rather than just repeating a cool-sounding quote that’s completely unmoored from reality.

Unfortunately, political partisans of all stripes and colors are guilty of frequently saying (and worse, believing) obviously illogical statements. Worse, politics can be important, so completely disengaging isn’t always a realistic option. How do you engage in politics without falling into illogic and sloppy thinking?

To be honest, I haven’t figured it out. Some ideas:

Substitute key words (whether in your head or out loud). When first hearing a slogan, don’t just think to yourself “this sounds right(eous)” or “this sounds false (evil).” Instead, think to yourself, “if I use near-synonyms for keywords in this slogan, will it immediately fall apart?”

“You can’t have a country without borders” sounds obviously correct and in line with historical experience, but if you instead say “you can’t have a country without immigration restrictions” suddenly it all sounds much more dubious.

Know things about the world. As I’ve said in an earlier post, critical thinking is built on a scaffolding of facts. Knowing lots of facts about the world makes it easy for you to see patterns and counterexamples, and less likely to be tricked by rhetorically beautiful arguments with zero empirical backing.

Employ standard critical thinking practices. Read opposing arguments, be charitable to your political opponents, don’t shy away from information that goes against your biases, etc. See the world as it is, not as you wish it to be.

Sounds basic, but sometimes the basics are good!

To paraphrase Descartes, “A mind without critical thinking will cease to be a mind.” So please subscribe to my substack for deepity-less thoughts! After all, great ideas are ever borderless.

Housekeeping & Thanks

Chiangsanity: Holy crap, the Ted Chiang review post really exploded! Front page of Hacker News and 24k views in under 48 hours??!!! The CEO of Substack subscribes to me now (hi Chris!)? Crazy!!

To new subscribers: don’t worry, my interests are very eclectic and I aim to have a wild oeuvre! Most posts will not be political content.

Paid subscriptions: I turned on paid subs because the substack algorithm promotes paid newsletters more (hi Chris!) and so people can show appreciation of my work. Nothing important will be paywalled.

An interesting mirror case here is the Chinese Hukou system. Within China, you need a household-registration Hukou to access schooling, healthcare, and other social services. This is effectively a within-country border for crossing into a new province or city. Despite this, China’s government is fairly centralized, and provincial governments overall have less sovereignty than U.S. states. So it’s possible to have BordersImmigrationRestriction without much BordersStateControl. This is another example of why the two meanings of “border” are practically, not just logically, separate.

In 1870, the % of US population that was foreign-born was 14.4%, almost identical to today.

I’m a connoisseur of rare logical fallacies, and I’m not sure I’ve actually seen this one before? I’ve seen dumb political deepities, but this specific “argument from homonym” logical structure might be a new one.

Really like the historical counterexamples! I’ll be adding this argument to my arsenal going forward. Well argued, and well done!

The issue is that travel is much, much easier now than it was in the past. You didn't need immigration restrictions when the fastest ways to get around were horses and sailboats.