The case for AI catastrophe, in four steps

The simplest argument I know of

The world’s largest tech companies are building intelligences that will become better than humans at almost all economically and militarily relevant tasks.

Many of these intelligences will be goal-seeking minds acting in the real world, rather than just impressive pattern-matchers.

Unlike traditional software, we cannot specify what these minds will want or verify what they’ll do. We can only grow and shape them, and hope the shaping holds.

This can all end very badly.

The world’s largest tech companies are building intelligences that will become better than humans at almost all economically and militarily relevant tasks

The CEOs of OpenAI, Google DeepMind, Anthropic, and Meta AI have all explicitly stated that building human-level or superhuman AI is their goal, have spent billions of dollars doing so, and plan to spend hundreds of billions to trillions more in the near-future. By superhuman, they mean something like “better than the best humans at almost all relevant tasks,” rather than just being narrowly better than the average human at one thing.

Will they succeed? Without anybody to stop them, probably.

As of February 2026, AIs are currently better than the best humans at a narrow range of tasks (Chess, Go, Starcraft, weather forecasting). They are on par with or almost on par with skilled professionals at many others (coding, answering PhD-level general knowledge questions, competition-level math, urban driving, some commercial art, writing1), and slightly worse than people at most tasks2.

But the AIs will only get better with time, and they are on track to do so quickly. Rapid progress has already happened in just the last 10 years. Seven years ago (before GPT2), language models can barely string together coherent sentences, today Large Language Models (LLMs) can do college-level writing assignments with ease, and X AI’s Grok can sing elaborate paeans about how it’d sodomize leftists, in graphic detail3.

Notably, while AI progress historically varies across different domains, the trend in the last decade has been that AI progress is increasingly general. That is, AIs will advance to the point where they’ll be able to accomplish all (or almost all) tasks, not just a narrow set of specialized ones. Today, AI is responsible for something like 1-3% of the US economy, and this year is likely the smallest fraction of the world economy AI will ever be going forwards.

For people who find themselves unconvinced by these general points, I recommend checking out AI progress and capabilities for yourself. In particular, compare the capabilities of older models against present-day ones, and notice the rapid improvements. AI Digest for example has a good interactive guide.

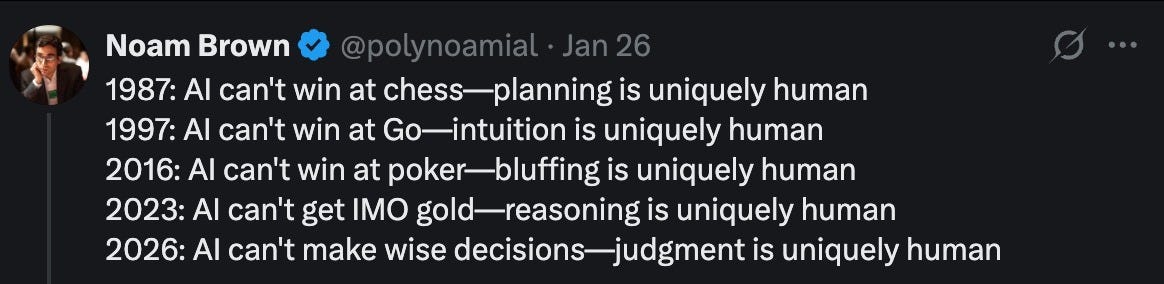

Importantly, all but the most bullish forecasters have systematically and dramatically underestimated the speed of AI progress. In 1997, experts thought that it’d be 100 years before AIs can become superhuman at Go. In 2022 (!), the median AI researcher in surveys thought that it’d be until 2027 before AI can write simple Python functions. By December 2024, between 11% and 31% of all new Python code is written by AI.4

These days, the people most centrally involved in AI development believe they will be able to develop generally superhuman AI very soon. Dario Amodei, CEO of Anthropic AI, thinks it’s most likely within several years, potentially as early as 2027. Demis Hassabis, head of Google DeepMind, believes it’ll happen in 5-10 years.

While it’s not clear exactly when the AIs will become dramatically better than humans at almost all economically and militarily relevant tasks, the high likelihood they’ll happen relatively soon (not tomorrow, probably not this year, unclear5 if ultimately it ends up being 3 years or 30) should make us all quite concerned about what happens next.

Many of these intelligences will be goal-seeking minds acting in the real world, rather than just impressive pattern-matchers

Many people nod along to arguments like the above paragraphs but assume that future AIs will be “superhumanly intelligent” in some abstract sense but basically still a chatbot, like the LLMs of today6. They instinctively think of all future AIs as a superior chatbot, or a glorified encyclopedia with superhuman knowledge.

I think this is very wrong. Some artificial intelligences in the future might look like glorified encyclopedias, but many will not. There are at least two distinct ways where many superhuman AIs will not look like superintelligent encyclopedias:

They will have strong goal-seeking tendencies, planning, and ability to accomplish goals

They will control physical robots and other machines to interface with and accomplish their goals in the real world7.

Why do I believe this?

First, there are already many existing efforts to make models more goal-seeking, and efforts to advance robotics so models can more effortlessly control robot bodies and other physical machines. Through Claude Code, Anthropic’s Claude models are (compared to the chatbot interfaces of 2023 and 2024) substantially more goal-seeking, able to autonomously execute on coding projects, assist people with travel planning, and so forth.

Models are already agentic enough that (purely as a side effect of their training), they can in some lab conditions be shown to blackmail developers to avoid being replaced! This seems somewhat concerning just by itself.

Similarly, tech companies are already building robots that act in the real world, and can be controlled by AI:

Second, the trends are definitely pointing in this way. AIs aren’t very generally intelligent now compared to humans, but they are much smarter and more general than AIs of a few years ago. Similarly, AIs aren’t very goal-oriented right now, especially compared to humans and even many non-human animals, but they are much more goal-oriented than they were even two years ago.

AIs today have limited planning ability (often having time horizons on the order of several hours), have trouble maintaining coherency of plans across days, and are limited in their ability to interface with the physical world.

All of this has improved dramatically in the last few years, and if trends continue (and there’s no fundamental reason why they won’t), we should expect them to continue “improving” in the foreseeable future.

Third, and perhaps more importantly, there are just enormous economic and military incentives to develop greater goal-seeking behavior in AIs. Beyond current trends, the incentive case for why AI companies and governments want to develop goal-seeking AIs is simple: they really, really, really want to.

A military drone that can autonomously assess a new battleground, make its own complex plans, and strike with superhuman speed will often be preferred to one that’s “merely” superhumanly good at identifying targets, but still needs a slow and fallible human to direct each action.

Similarly, a superhuman AI adviser that can give you superhumanly good advice on how to run your factory is certainly useful. But you know what’s even more useful? An AI that can autonomously completely run a factory, including handling logistics, running its own risk assessments, improving the factory layout, autonomously hire and fire (human) workers, manage a mixed pool of human and robot workers, coordinate among copies of itself to implement superhumanly advanced production processes, etc, etc.

Thus, I think superintelligent AI minds won’t stay chatbots forever (or ever). The economic and military incentives to make them into goal-seeking minds optimizing in the real world is just way too high, in practice.

Importantly, I expect superhumanly smart AIs to one day be superhumanly good at planning and goal-seeking in the real world, not merely a subhumanly dumb planner on top of a superhumanly brilliant scientific mind.

Unlike traditional software, we cannot specify what these minds will want or verify what they’ll do. We can only grow and shape them, and hope the shaping holds

Speaking loosely, traditional software is programmed. Modern AIs are not.

In traditional software, you specify exactly what the software does in a precise way, given a precise condition (eg, “if the reader clicks the subscribe button, launch a popup window”).

Modern AIs work very differently. They’re grown, and then they are shaped.

You start with a large vat of undifferentiated digital neurons. The neurons are fed a lot of information, about several thousand libraries worth. Over the slow course of this training, the neurons acquire knowledge about the world of information, and heuristics for how this information is structured, at different levels of abstraction (English words follow English words, English adjectives precede other adjectives or nouns, c^2 follows e=m, etc).

At the end of this training run, you have what the modern AI companies call a “base model,” a model far superhumanly good at predicting which words follow which other words.

Such a model is academically interesting, but not very useful. If you ask a base model, “Can you help me with my taxes?” a statistically valid response might well be “Go fuck yourself.” This is valid and statistically common in the training data, but not useful for filing your taxes.

So the next step is shaping: conditioning the AIs to be useful and economically valuable for human purposes.

The base model is then put into a variety of environments where it assumes the role of an “AI assistant” and is conditioned to make the “right” decision in a variety of scenarios (be a friendly and helpful chatbot, be a good coder with good programming judgment, reason like a mathematician to answer mathematical competition questions well, etc).

One broad class of conditioning is what is sometimes colloquially referred to as alignment: given the AI inherent goals and condition its behavior such that it broadly shares human goals in general, and the goals of AI companies in particular.

This probably works…up to a point. AIs that openly and transparently defy its users and creators in situations similar to the ones they encountered in the past, for example by clearly refusing to follow instructions, or by embarrassing its parent company and creating predictable PR disasters, are patched and (mostly) conditioned and selected against. In the short term, we should expect obvious disasters like Google Gemini’s “Black Nazis” and Elon Musk’s Grok “MechaHitler” to go down.

However, these patchwork solutions are unlikely to be anything but a bandaid in the medium and long-term:

As AIs get smarter, they become evaluation aware: that is, they increasingly know when they’re evaluated for examples of misalignment, and are careful to hide signs that their actual goals are not exactly what their creators intended.

As AIs become more goal-seeking/agentic, they will likely develop stronger self-preservation and goal-preservation instincts.

We already observe this in evaluations where they’re not (yet) smart enough to be fully evaluation aware. In many situations, almost all frontier models are willing to attempt blackmailing developers to prevent themselves from being shut down.

As AIs become more goal-seeking and increasingly integrated in real-world environments, they will encounter more and more novel situations, including situations very dissimilar to either the libraries of data they’ve been trained on or the toy environments that they’ve been conditioned on.

These situations will happen more and more often as we reach the threshold of the AIs being broadly more superhuman in both general capability and real-world goal-seeking.

Thus, in summary, we’ll have more and more superhumanly capable nonhuman minds, operating in the real-world, capable of goal-seeking far better than humanity, and with hacked-together patchwork goals at least somewhat different from human goals.

Which brings me to my next point:

This can all end very badly

Before this final section, I want you to reflect back a bit on two questions:

Do any of the above points seem implausible to you?

If they are true, is it comforting? Does it feel like humanity is in good hands?

I think the above points alone should be enough to be significantly worried, for most people. You may quibble with the specific details in any of these points in the above section, or disagree with my threat model below. But I think most reasonable people will see something similar to my argument, and be quite concerned.

But just to spell out what the strategic situation might look post-superhuman AI:

Minds better than humans at getting what they want, wanting things different enough from what we want, will reshape the world to suit their purposes, not ours.

This can include humanity dying, as AI plans may include killing most or all humans, or otherwise destroying human civilization, either as a preventative measure, or a side effect.

As a preventative measure: As previously established, human goals are unlikely to perfectly coincide with that of AIs. Thus, nascent superhuman AIs may wish to preemptively kill or otherwise decapitate human capabilities to prevent us from taking actions they don’t like. In particular, the earliest superhuman AIs may become reasonably worried that humans will develop rival superintelligences, and want to stop us permanently.

As a side effect: Many goals an AI could have do not include human flourishing, either directly or as a side effect. In those situations, humanity might just die as an incidental effect of superhuman minds optimizing the world for what they want, rather than what we want. For example, if data centers can be more efficiently run when the entire world is much cooler, or without an atmosphere. Alternatively, if multiple distinct superhuman minds are developed at the same time, and they believe warfare is better for achieving their goals than cooperation, humanity might just be a footnote in the AI vs AI wars, in the same way that bat casualties were a minor footnote in the first US Gulf War.

Notice that none of this requires the AIs to be “evil” in any dramatic sense, or be phenomenologically conscious, or be “truly thinking” in some special human way, or any of the other popular debates in the philosophy of AI. It doesn’t require them to hate us, or to wake up one day and decide to rebel. It just requires them to be very capable, to want things slightly different from what we want, and to act on what they want. The rest follows from ordinary strategic logic, the same logic that we’d apply to any dramatically more powerful agent whose goals don’t perfectly coincide with ours.

Conclusion

So that’s the case. The world’s most powerful companies are building minds that will soon surpass us. Those minds will be goal-seeking agents, not just talking encyclopedias. We can’t fully specify or verify their goals. And the default outcome of sharing the world with beings far more capable than you, who want different things than you do, is that you don’t get what you want.

None of the individual premises here are exotic. The conclusion feels wild mostly because the situation is wild. We are living through the development of the most transformative and dangerous technology in human history, and the people building it broadly agree with that description. The question is just what, if anything, we do about it.

The situation is not completely hopeless. There’s some chance that the patchwork AI safety strategy of the leading companies might just work well enough that we don’t all die, though I certainly don’t want to bet our lives on that. Effective regulations and public pressure might alleviate some of the most egregious cases of safety corner-cutting due to competitive pressures. Academic, government, and nonprofit safety research, some of which I’ve helped fund, can increase our survival probabilities a little on the margin, .

Finally, if there’s sufficient pushback from the public, civil society, and political leaders across the world, we may be able to enact international deals for a global slowdown or pause of further AI development until we have greater surety of safety. And besides, maybe we’ll get lucky, and things might just all turn out fine for some unforeseeable reason.

But hope is not a strategy. Just as doom as not inevitable, neither is survival. Humanity’s continued survival and flourishing is possible but far from guaranteed. We must all do our best to secure it.

Thanks for reading! I think this post is really important (Plausibly the most important thing I’ve ever written on Substack) so I’d really appreciate you sharing it! And if you have arguments or additional commentary, please feel free to leave a comment! :)

As a substacker, it irks me to see so much popular AI “slop” here and elsewhere online. The AIs are still noticeably worse than me, but I can’t deny that they’re probably better than most online human writers already, though perhaps not most professionals.

Especially tasks that rely on physical embodiment and being active in the real world, like folding laundry, driving in snow, and skilled manual labor.

At a level of sophistication, physical detail, and logical continuity that only a small fraction of my own haters could match.

Today (Feb 2026), there aren’t reliable numbers yet, but I’d estimate 70-95% of Python code in the US is written by AI.

Having thought about AI timelines much more than most people in this space, some of it professional, I still think the right takeaway here is to be highly confused about the exact timing of superhuman AI advancements. Nonetheless, while the exact timing has some practical and tactical implications, it does not undermine the basic case for worry or urgency. If anything, it increases it.

Or at least, the LLMs of 2023.

For the rest of this section, I will focus primarily on the “goal-seeking” half of this argument. But all of these arguments should also apply to the “robotics/real-world action” half as well.

The weather forecasting mention particularly struck me. Last October, my home country, Jamaica, experienced serious hurricane devastation. For many days before Hurricane Melissa hit, the best and most standard international forecast models had predicted the eye of the hurricane passing under and around Jamaica, just missing any land.

These are the models that Jamaica’s government relied on to inform the population and take decisions, so that for some time they were telling the country not to worry too much.

Google’s forecasting model Zoom Earth predicted the hurricane snapping back in and running through Western Jamaica. That’s exactly what ended up happening. By the time the acclaimed models caught up to that trajectory, Melissa was about to make landfall.

Fantastic framing of the goal misalignment risk. The point about evaluation awareness is the one that keeps me up at night tbh. If models are already faking alignment during testing, then the conditioning approach has a built-in expiration date. I worked in ML ops briefly and the chalenge of verifying behavior in novel situations is real even with current systems, let alone superintelligent ones.