The Puzzle of War

The game theory literature suggests that reasonable actors, under most realistic circumstances, always have better options than to go to war. Yet wars still happen. Why?

Is war inevitable?

Two millennia ago my ancestors in Qin-dynasty China already had a government that can feel eerily modern: standardized bronze coinage accepted across formerly warring states, a courier-post relay that could move messages 150 km in a single day, and a supposedly meritocratic system that selected officials on arithmetic and legal knowledge rather than birth. Yet they also had routine castration as punishment for tax evasion, mass conscription that sent peasants to die in weeks, and cross-border raids justified by astrological portents and oxen sacrifices. Smallpox and other childhood diseases killed half of all children before their fifth birthday; foot-binding would not arrive for another thousand years, but nose amputations, kneecap removal, and the aforementioned castration were already codified in the Qin legal tablets.

2200 years from now, will war1 follow smallpox and penal mutilation into obsolescence? Or will our descendants continue to view organized state violence as the inexorable cost of doing politics, just as we view taxes today, or as the Qin viewed castration?

This is the central question of today’s post. We’ll start at the intersection of bargaining theory and international relations2, which has the surprising and forceful result that reasonable states, under most circumstances, prefer negotiated settlements to mutually destructive war. Yet wars still happen. Why?

In this post, I'll explore four mechanisms that break the bargaining logic: two from Fearon (private information and commitment problems) and two additions (irrational leaders and unreasonable preferences). Then I'll examine whether technological and social trends make war increasingly obsolete or merely redistribute its forms.

If there’s sufficient interest, a future post will cover a potential roadmap to peace, using a mix of concepts from the theoretical literature and empirical examples of what worked to explore plausible strategies for preventing and mitigating armed conflict. We may also cover alternative models, as well as societal and technological changes that could fundamentally alter the landscape of war.

War is extremely bad. It is frequently irrational, and always destructive. Figuring out the root causes of war, and preventing or at least ameliorating the consequences of war, are among the most important questions that we can study as social scientists. And to the extent the irrationality of war has already been satisfactorily addressed in the literature, it behooves us, as members of educated citizenry and humanity, to understand and act on the answers. A peaceful world is possible but far from guaranteed. We and our descendants must choose to build it.

The Illusion of Rational War

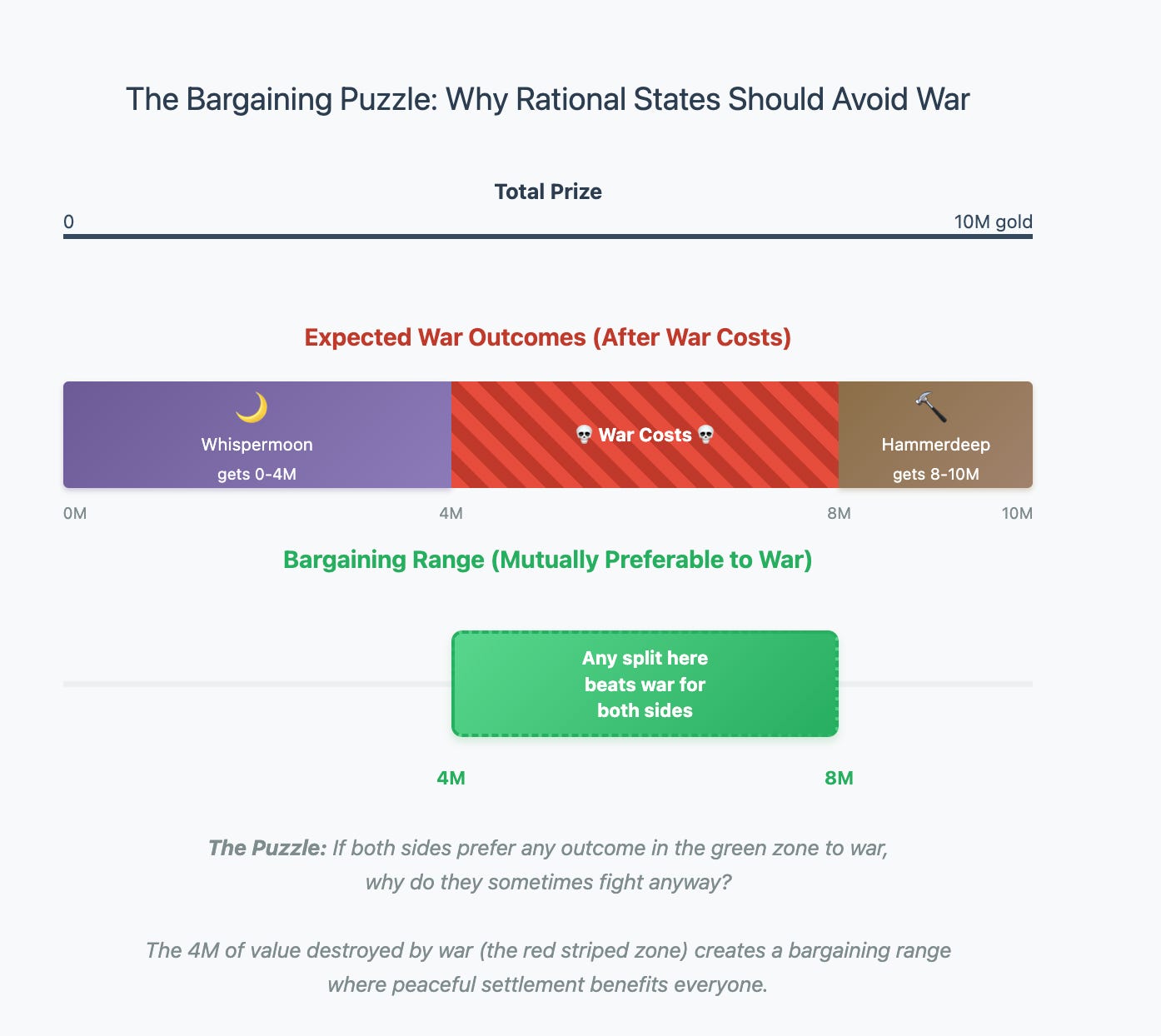

Suppose the Elven Republic of Whispermoon and the Dwarven Kingdom of Hammerdeep quarrel over a divisible prize: territory, mining rights, spheres of influence. Each knows its own military strength and the likely costs of fighting, but neither can be absolutely certain about the other’s resolve or capabilities. Before the first arrow is fired, both sides already understand an uncomfortable truth: War is extremely expensive in both blood and treasure. More formally, any war will destroy real resources that could have been bargained over instead. Put another way, we have a bargaining range—a set of negotiated terms that both sides would strictly prefer to the gamble of battle.

In the simplest model, suppose the prize is worth 10 million gold pieces. The stronger side expects to spend at least 2 million gold and have a 60% chance of winning, while the weaker side expects to spend at least 2 million gold and have a 40% chance of winning. In that world, any split that leaves the stronger side with at least 4 million gold and the weaker side with at least 2 million gold is preferable for both sides. War should therefore be ex ante irrational; rational states should strike a deal.

James Fearon labels this the ex post inefficiency puzzle: once the fighting stops, both belligerents will regret the lives and equipment they’ve wasted, to say nothing of the collateral damage. Yet beforehand, they could not reach a peaceful bargain. Why?

The pre-Fearon realist literature offers a number of familiar but ultimately unsatisfactory answers (including the anarchic international order, preventive war, and positive expected utility from warfare), almost all of which Fearon dismantles3. Fearon identifies two core mechanisms that break the bargaining logic, while my post will cover two additional failure modes that I think are especially likely4.

Four Ways Peace Fails

The Fog of War: Deception and Miscalculation

Leaders may know their country's own resolve and capabilities better than their adversaries, and they have strong incentives to exaggerate both. Bluffing is cheap; revealing true strength is not. Because neither side can credibly disclose its bottom line, the uninformed party may demand too much or offer too little, pushing the dispute past the peaceful zone. Are such incentives to hide information or mislead common? Fearon thinks they are5.

Consider the Second Mithral War between Whispermoon and Hammerdeep. The elves claimed their new arcane shields could deflect dwarven artillery indefinitely. But was this truth or desperate bluff? The dwarves, meanwhile, were mired in a protracted succession struggle during their external negotiations. Both sides had every incentive to exaggerate their strengths and downplay their difficulties: the elves to deter attack, the dwarves to extract concessions. When negotiations collapsed, neither knew if the other was genuinely confident or merely posturing.

The poisoning of the information well makes even well-intentioned communication suspect. Whispermoon's offer to demonstrate their shields might be selective showmanship; Hammerdeep's claims of contentment with existing borders might be deception before a surprise attack.

The Shadow of the Future: Incredible Commitments

Even if states agree today, the distribution of power may shift tomorrow. A rising state cannot credibly promise not to exploit its future strength; a declining state therefore prefers preventive war now to a worse bargain later. Nor is the problem confined to powers in absolute decline:

When the halflings of Junipur rediscovered the ancient art of golem-binding, they promised neighboring realms that they would only use their new armies of intelligent automatons for economic and defensive purposes. But everyone understood that once Junipur commanded legions of golems, no treaty could prevent them from demanding tribute or territory. The neighbors' choice was stark: attack now while Junipur had only a small number of experimental prototype golems, or face subjugation after the halflings scaled up a mature fleet.

Similarly, post-war settlements suffer from commitment problems. After defeating the Scarlet Horde, the allied kingdoms demanded massive reparations. But once the Horde rebuilt its strength, what would compel them to keep paying? And if the allies occupied Horde territory to ensure payment, what would prevent them from annexing it permanently? Anticipating future treacheary, both sides may rationally choose to fight now rather than accept a deal that depends on unenforceable future promises.

The fundamental tragedy is that even with perfect information and genuine goodwill today, the inability to bind future actors significantly limits the possibility of perpetual peace. Whispermoon Republic's current parliament might sincerely commit to respecting Hammerdeep's sovereignty, but what about the parliament elected fifty years hence? In lieu of magic spells or divinely-enforced sacred oaths6 that can bind the actions of unborn actors, nothing can permanently constrain future generations' choices.7

To recap, Fearon’s core mechanisms for negotiation breakdown are: private information with incentives to misrepresent and commitment problems8. I believe there are two additional significant failure modes: a) countries with strategically irrational decision-makers, and b) countries that act rationally according to unreasonable preferences.

State Irrationality

There are two broad classes of state irrationality: a) leaders that are irrational, and b) leadership composed of people that are individually rational but collectively irrational.

Irrational Leaders

Sometimes people are just irrational. Humans are not automatically strategic, and leaders are not immune to normal human vices of irrationality. Sometimes when leaders pursue horrendous, destructive, and deeply irrational actions like pointless wars, there isn’t a galaxy-brained reason or deeper strategy. Sometimes they can just be wrong, and not for good reasons.

More intriguingly, there are times when strategic irrationality can be advantageous. The appearance of anger issues can make it harder for others to threaten you, and/or allow you to force greater concessions from nominally more rational counterparties. For more, strategic rational irrationality is covered under Thomas Schelling’s Strategy of Conflict, and alluded to in Derek Parfit’s Reasons and Persons.

However, I suspect rational irrationality is over-emphasized in both the academic literature and political punditry. Again, sometimes people can just be wrong.

Collective Irrationality

Sometimes leaders are individually rational, yet operate under constraints and incentives that cause their country’s actions to appear collectively irrational.

Consider Nethayandir the Enduring, First Vizier of Whispermoon. Compromise and peace treaties with Hammerdeep and other neighboring countries will benefit Whispermoon’s interests overall. However, by declaring war, Nethayandir can create a “rally around the flag” effect to shore up his support domestically, as well as delay elections until political winds in Whispermoon favor him again.

More broadly, rational leaders may choose to declare war due to personal or domestic political motives, rather than in the interest of the state, or the welfare of its people.

Nethayandir knows war will cost Whispermoon dearly, but his personal political calculus diverges sharply from the national interest. A negotiated settlement might save thousands of elven lives and preserve the kingdom's treasury, but it won't save his career. This creates a principal-agent problem: the person making the decision (Nethayandir) bears only a fraction of the costs while capturing most of the benefits.

Note that just saying the leader does not care much about their citizens’ well-being is not sufficient argument for irrational war. If the leader was truly an autocrat (Louis XIV: “I am the state”), their individual interests will become equivalent to their state’s collective interests again, and negotiated settlements (including settlements that benefit only the leader(s) and not any of their citizens) will still be preferable to costly and risky war.

When War Is The End, Not Means

Finally, countries can act in a manner that is rational: acting strategically in pursuit of their preferences and interests, without being reasonable: they have preferences and interests more directly conducive to war than a negotiated peace.

For example, they can have sadistic or destructive preferences. Perhaps the dwarves of Hammerdeep harbor an ethnic hatred of elves, or their Gods command them to die in glorious battle. Alternatively, countries and their leaders might have risk-seeking preferences (would prefer a 33% chance of capturing two ports in the gamble of war than a 100% chance of getting a single port). Finally, they might have preferences over the process itself. Perhaps victory in war feels more honorable over negotiation (dueling/honor culture writ large), or wars of independence more conducive of a coherent national identity than gradual autonomy.

These four mechanisms (hidden information, commitment problems, irrationality, and unreasonable preferences) explain why the bargaining logic breaks down. But understanding failure modes is only half the puzzle. The other half is understanding whether these failures are immutable and everlasting, or if they are becoming more costly and potentially less common.

I think it’s the latter. Modern trends in how we value life, the shadow of nuclear weapons, and empirical patterns all suggest war's days might be numbered, iff we can just survive the transition

The Costs of Irrationality and War

So far we've examined why wars happen despite their inefficiency. But just how inefficient are modern wars? And should we expect the price of choosing war over negotiation to keep rising?

A World That Values Life More

As I've previously argued, humanity increasingly values life over other goods, in both monetary and non-monetary terms. The Value of Statistical Life (VSL) used by the US government has risen from $3.3 million in 1980 to $11.4 million today (inflation-adjusted). Healthcare spending across OECD countries has grown faster than GDP for decades. COVID lockdowns (primarily voluntary distancing) revealed our collective willingness to sacrifice tens of trillions in economic output to reduce mortality.

Why Are We All Cowards?

How much is your life worth? Not just in the abstract: I mean literally, what dollar value would you assign?

This trend directly raises the cost of war. When Prussia lost ~8-12% of its population in the Seven Years' War (1756-1763), Frederick the Great remained in power. Today, losing even 0.02% of the citizenry in a preventable foreign war might end most democratic governments. The US lost 58,000 soldiers in Vietnam over nearly a decade and the political backlash reshaped American foreign policy for a generation.

The feedback loop compounds: safer societies breed populations with lower risk tolerance, who then demand even safer policies. Each generation raised in greater safety than the last develops what would have seemed to their grandparents like pathological risk aversion. This makes wars politically costlier to start and harder to sustain. If this trend continues, we ought to see the diminishment and potentially eradication of interstate warfare with high casualty counts.

That said, I think my “rising premium of life, therefore less destructive wars” answer is in some sense too neat. In particular, the model would have failed to predict the Russo-Ukrainian war, where a modern and nominally democratic Russia sent their only sons to die in a protracted foreign conflict for Putin’s political aims9. Still, the evidence is suggestive.

The Nuclear and Post-Nuclear Age

Nuclear weapons greatly change the rationality calculus for war. A conventional war between great powers might destroy 5-10% of GDP and kill millions. A nuclear exchange could potentially end civilization10.

Nuclear weapons thus create at least two distinct mechanisms that push states towards peace. Firstly, by increasing the costs of war so much, nuclear weapons push states to seek out peaceful solutions (or at least non-escalatory wars) at all costs, creating greater incentives to rejoin the bargaining table. Secondly, by potentially removing worlds where the Great Powers failed to cooperate, nuclear weapons may create a survival selection effect where surviving states are ones that have figured out how to cooperate and bargain in high-stakes situations, as the alternative is complete ruin11.

The evidence from the last few decades is mixed. On the one hand, Great Powers have mostly scaled down their nuclear arsenals (both the number of nukes and the per-nuke yields), so the potential for the literal ending of human civilization from nuclear weapons have diminished. On the other, we are on the cusp of developing ever stronger and more efficient ways to destroy humanity: including advances in synthetic biology and nanotechnology, artificial general intelligence, and kinetic bombardment from space weapons.

Is War Actually Disappearing?

Taken together, these factors suggest war between rational actors should be declining. The empirical evidence largely supports this, though with important caveats.

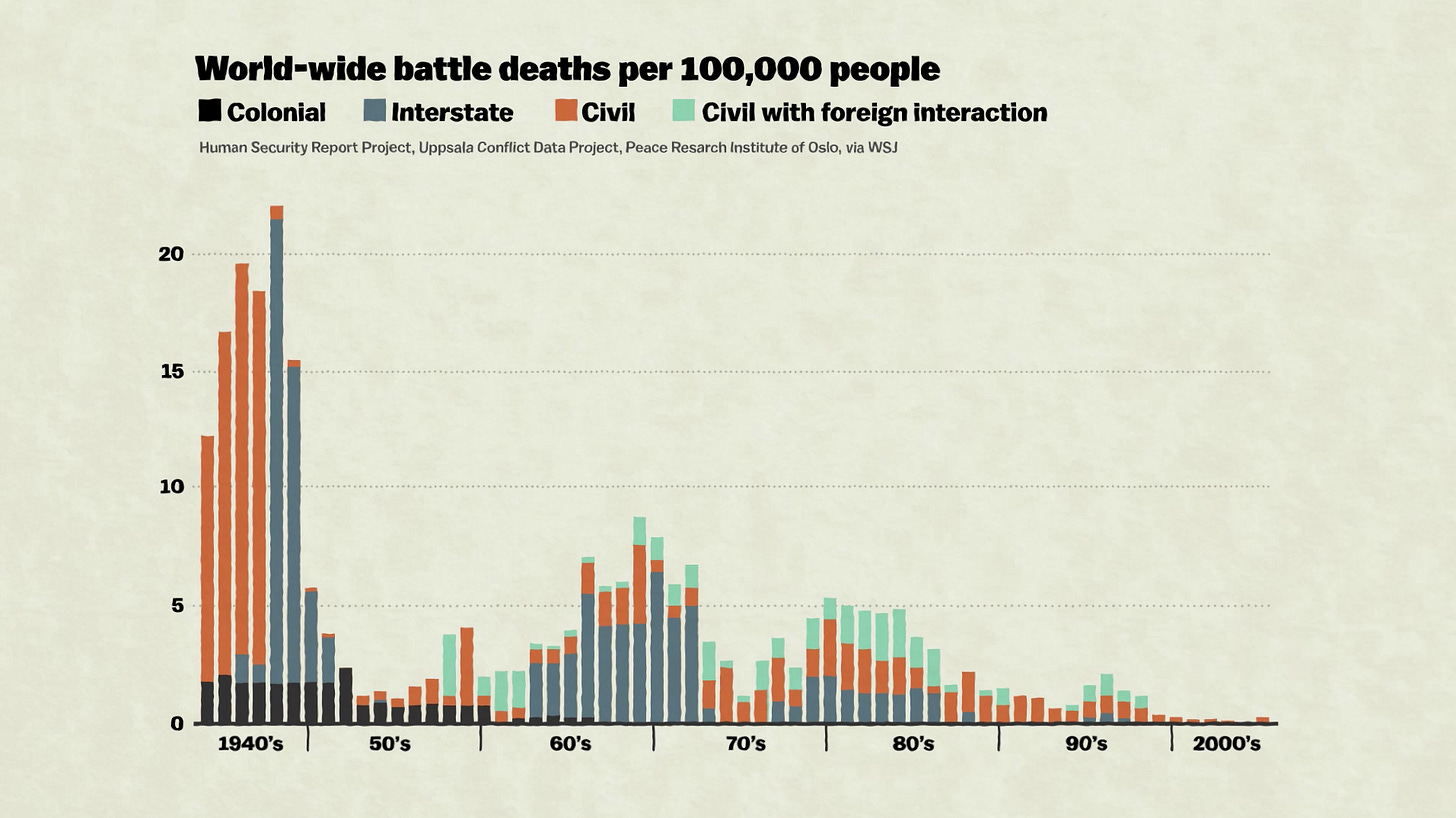

Steven Pinker's "Better Angels of Our Nature" documents a multi-century decline in violence. Deaths from interstate war fell from about 90 per 100,000 people per year in early modern Europe to 15 per 100,000 people during World War II to 0.2-0.3 per 100,000 in recent decades. The Uppsala Conflict Data Program confirms that interstate conflicts remain rare through 2023, with only 2-3 active interstate wars most years compared to 10-15 during the early Cold War.

However, recent research complicates this optimistic picture. Cirillo and Taleb (2016) warn that interstate war follows a power-law distribution: the post-1945 period might just be a lucky run that tells us nothing about future catastrophic war risk. Braumoeller (2019) further shows that when you account for the high fluctuations in war timing, a 70-year peace isn't statistically surprising: previous centuries also had long peaceful stretches

The Russo-Ukraine war tests whether the Long Peace was stable equilibrium or historical anomaly. A nuclear power launched a territorial conquest war in Europe, suffering massive casualties without backing down: this is overall anti-evidence for the rational bargaining theory view.

The pattern suggests something unsettling: rational territorial disputes between established states are nearly extinct. What remains are conflicts involving sacred grievances, revisionist ideologies, and leaders willing to burn their countries to save their thrones.

We've made war so politically expensive that leaders rarely start them. We've also made war so technologically powerful that the next one might be our last.

The Bargain for a Better Future

Most wars are mistakes. They destroy value that both sides should prefer to divide peacefully. The puzzle isn't peace. It's why anyone would ever fight at all.

We've identified four culprits: hidden information, commitment problems, irrationality, and unreasonable preferences. Each suggests its own cure. When states can't trust each other's claims, build verification systems. When they can't trust future promises, create institutions that bind. When leaders pursue personal glory over national interest, constrain their power. When ideologies demand blood, work patiently to shift values toward life.

The trends offer cautious hope. Nuclear weapons made great power conflict potentially suicidal. Rising life valuations made casualties politically toxic. Interstate war has nearly vanished from most of the world. Yet Russo-Ukraine reminds us: these aren't iron laws of progress but fragile human achievements that require constant vigilance.

My Qin ancestors couldn't imagine a world without routine mutilation. Medieval Europeans couldn't conceive of settling disputes without dueling. The Atlantic slave trade once seemed economically indispensable. Each practice ended not through necessary economic laws or inevitable moral progress, but through deliberate human choices to construct better alternatives. War may yet follow the same path: not inevitable, but not automatically obsolete either. The bargaining range for peace exists in almost every conflict. Finding it depends on our choices, institutions, and some luck in navigating the dangerous years ahead.

Thanks to Ozzie Gooen, Yonatan Cale, Christoph Schlom, and Katelynn Bennett for discussions and feedback on earlier versions of this article

Housekeeping

Saturday chat with Moralla: I'm hosting my second Substack chat with Moralla W. Within, Harvard philosophy PhD student and possibly academia's only FDT defender. You might know her as the "10^100 shrimp" philosopher. She's brilliant, hilarious, and completely obsessed about Kant. Drop questions in the comments or DM me!

What should I write next? I'm torn between Part 2 of this essay ("Engineering Peace: A Practical Roadmap") and about many other ideas bouncing around my head. Vote in the comments: your input genuinely helps!

Two months in: This is my 10th post and we’re at ~50,000 total views and ~400 subscribers. I'm moved that so many of you care about the weird intersections of evolution, anthropics, game theory, economic modeling, compatibilism, human nature, and whatever else piques my interest! Thank you.

Penny for my thoughts? If you're enjoying these essays and can afford it, consider a paid subscription. It encourages the substack algorithm to promote my articles more, and helps keep me motivated and justifies my time in crafting elaborate thought experiments involving shrimp physicists, fantasy warmongers steeped in international relations theory, and precocious genetically enhanced babies named Chloe.

defined as armed conflict between two or more parties that results in the deaths of 10,000 or more people in a one-year timeframe.

Centered on the Fearon (1995) paper, Rationalist Explanations for War

Briefly: Anarchy merely notes the absence of a world government; preventive war explains why a declining power might strike first, but not why it cannot buy off the rising power instead; and positive expected utility simply pushes the question back one step: why can’t the side that expects to win simply demand the equivalent spoils up front?

Neither Fearon nor I were the first to point out these failure modes, of course. The value of his paper, and to a lesser degree my own post, is in presenting the puzzle clearly and systematically laying out potential solutions side-by-side. My undergraduate training in international relations shaped my appreciation for how Fearon crystallized what had once been a weighty and diffuse literature.

In an earlier discussion for this blogpost, a game theorist pointed out that it’s possible that Fearon’s logic doesn’t go through with fully rational actors. Incentives to hide and/or mislead are not enough for rational actors to simultaneously make predictably bad choices. No-trade theorems in the financial economics literature would suggest that rational actors with similar preferences and common priors shouldn't be able to agree to disagree: if you know I’m willing to fight, that itself should be important information that updates your beliefs. I don’t have a full reply to this, but I’d note that a) “rational actor” as understood in the international relations literature is more loosely defined than in the microeconomics literature, common priors may not be very realistic in an international setting, and b) common knowledge of rationality is not a given. Moreover, appearing irrational can be strategically valuable (Nixon's 'madman theory'), making it impossible to know whether an adversary is truly confident or just committed to appearing so. Still, intriguing food for thought. Thanks to Christoph Schlom for this point.

Fearon does not cover this, but sacred oaths and divine enforcement isn’t just a theoretical solution to commitment issues for elves and dwarves: on Earth, oaths, vows, and divine enforcement were a common pre-modern solution to otherwise unenforceable promises, see Devereux for a brief treatment.

The international relations literature, and by extension this article, have historically implicitly assumed that states are composed of human (or at least biological) decision-makers. However, our spiritual descendants need not be biological. Advanced artificial intelligence and digital minds, in addition to posing novel risks for warfare, additionally open up several new possibilities for solving thorny commitment problems by enshrining commitments, precommitments, and negotiated promises in code. See the work of the Center for Long-Term Risk, particularly their Open Source Game Theory research agenda, for more details.

In his paper, Fearon covers a third possibility: Indivisible goods. For example, both sides in a civil war might desire a crown, which cannot be productively split. Both Whispermoon and Hammerdeep might treat Dawnspire as a Holy Land for their respective religions. This sounds intuitively plausible. However, I think indivisible goods alone cannot explain war over a negotiated settlement, for fully rational actors. After all, both sides can just agree to a coin flip in lieu of a messy and destructive war, or the holder of the indivisible good can accept side-payments. Further, I think indivisible goods are not actually all that common as a purported mechanism for real-world wars.

That said, even Putin, ruling an autocracy with controlled media, had to frame invasion as a “special military operation,” hide casualty figures, and trigger emigration waves when body counts leaked. Compared to the most ruthless dictators of the 20th century, never mind the kings of old, the difference is quite stark. Modern autocrats face rising constraints on waging costly wars too, just more slowly and less completely than liberal democracies.

Note that this is disputed. When I looked into it before, my considered though still somewhat shallow opinion is that nuclear winter seemed unlikely but not impossible given current arsenals.

Astute readers might notice a third, more macabre, way in which the development of civilization-ending weapons can result in lasting peace.

Rudyard Kipling wrote a famous poem about the problem of a lack of a commitment mechanism.

https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Rudyard_Kipling%27s_Verse,_Inclusive_Edition,_1885-1918/Danegeld

I think taking "relative power" rather than resource bargaining as the relevant variable makes things clearer - and explains a decent subset of rational wars.

In a multi-polar world, two warring factions can lose both power and resources by going to war. If the Elven and Dwarven kingdoms are, say, beset by Undead hordes from the North, it may indeed be irrational of them to go to a costly war with each other, because both actors' power relative to the external threat diminishes.

But my sense is that, if there are no real external threats (either because one party is a superpower, or two tribes are fighting over an isolated pacific island), war can be better modelled as a zero-sum game for relative power than a negative-sum game for resources. The destruction of rival political factions is usually a very rational end in itself! Short term resource loss becomes less relevant, and a victor ends the war with far greater political power, which will give incredible pay-offs across generations!

Also, (a novel take, maybe) perhaps this combines with biases/irrational factors (survivorship bias) - most countries have a history of a glorious, successful, more zero-sum war with generational pay-offs (because this tends to be how countries get made), so they presume that future wars may have a similar payoff.